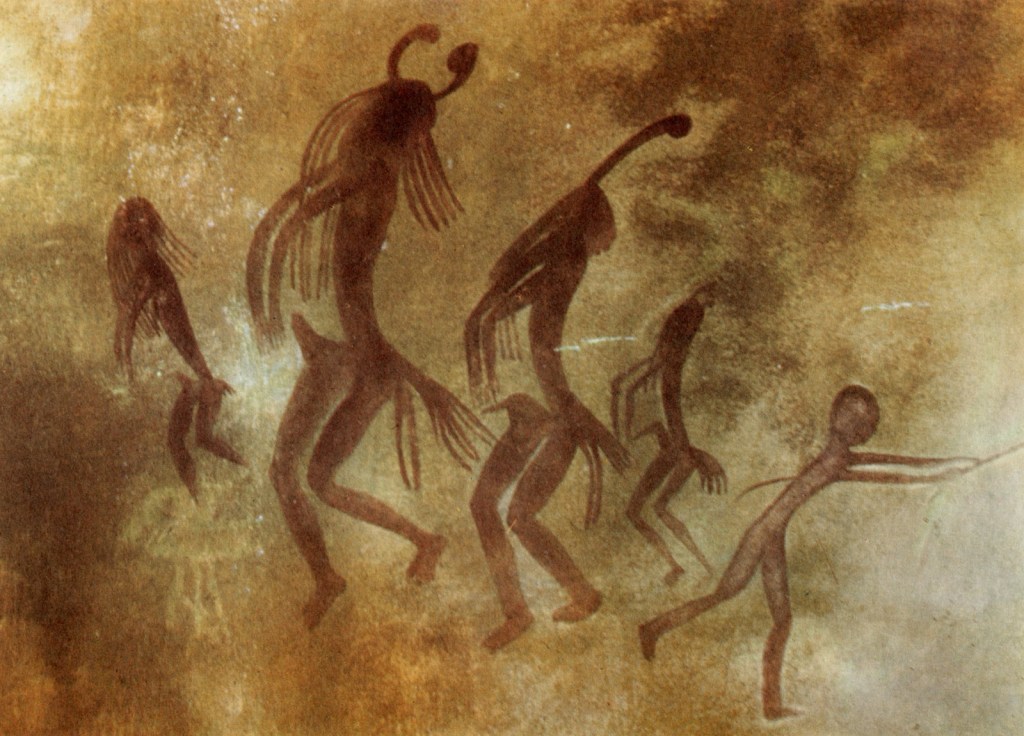

Experience wild, primordial rhythmic drives in this wild ride for concert band reminiscent of engaging ancient dances!

IMAGO DEI

Aphrodite, a goddess within the Greek pantheon, was a being of unparalleled beauty and charm. She was the governess of romantic love and had innumerable suitors.

In order to prevent the god of Olympus from destroying each other to earn her hand, Zeus decided that she should marry Hephaestus, the humble blacksmith.

The marriage was not to work. While Hephaestus labored in his forge to make sublime jewelry for his wife, Aphrodite frequently entertained male suitors, including the god Ares.

She was vain, ill-tempered, and easily offended. The beauty on the surface was often used to manipulate mortals (and even gods) to commit evil deeds.

The myth of Aphroditie is more than just an ancient story. It is a universal archetype for any whose apparent “beauty” (whether physical or intellectual) causes us to act in ugly ways—ways we know, deep in our own hearts, are wrong. And yet we surrender…

In the end, who is to blame? The heart of beauty or the heart of weakness?

Sometimes a piece you wrote a long time ago gets a new crack at life. That’s what I’m hoping with my sax quartet. It was a student work and not bad as it was, but I’ve given myself the opportunity to take another swing at it, shine it up, fix the quirks, and really make it what it was meant to be.

A perfect recital or concert piece for advanced quartets presented in four movements. Enjoy!

Well, maybe not quite Stockhausen-y things here, but definitely not the strict serialistic procedures of Schoenberg et al...

Composition methods, generally speaking, are as “simple” or “complex” as you choose to make them. If you want non-tonal methods of composing that don’t rely on a 12-tone row and its basic operations, I have a few ideas here you can play around with that other composer have found fruitful. Drop me a line here or wherever this article was posted with your own ideas–I’d love to hear them!

The first method involves manipulating intervals. The particular pitches come about as a result of these intervallic relationships.

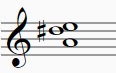

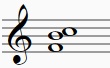

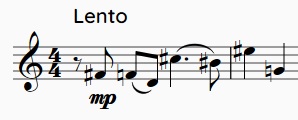

Here’s one method based on choosing a set of three intervals. Let’s say you wanted to compose a piece that was based around the augmented fourth, the perfect fifth, and the minor second. We choose pitches that fit this description and array them like so:

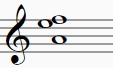

As you can see, there is present all three of our desired intervals. To base a piece of any length on three pitches can of course be done, but most prefer some additional variation. Let’s see what happens when we invert our set of original pitches:

Now we have two additional pitches that stem from our original set. The transposition operation of course can lead in many directions, but let’s do just one to keep our hypothetical piece nice and “tight.”

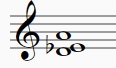

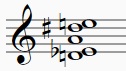

We might also take our original set and expand its compass (i.e., open it up):

You’ll note the augmented fourth was “expanded” into a perfect fifth while we retained the minor second. We could also do the opposite operation, contract the original compass:

Here the augmented fourth was “contracted” into a major third and the perfect fifth was contracted to a perfect fourth.

A more complex operation involves mirroring the original set around an axis (we’ll pick the pitch A):

You might observe that, in this case, this is simply the original set combined with the inversion we came up with above.

Let’s compose a little bit with these ideas to illustrate:

The red region uses the pitches of the original set. The blue region uses the inversion set (note that overlapping is fine). The yellow region uses the transposition of the original set. The pink region uses the expansion version of the original set. The dark green region uses the contracted version of the original set.

Of course this is very simple for illustrative purposes. Use your imagination to figure out ways to implement your sets.

We can see even from this though that, although differing pitches are used, they are all based on the same interval seeds. That is what gives this manner of composition it’s sense of cohesion.

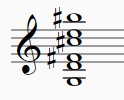

Another method (because I promised you more than one) involves taking a chord you like and using it as the basis for melodic material (and also, presumably, accompanimental materials):

We have a chord build of thirds and fifths. We could use this to make a melodic line:

All of the pitches in that line came out of our chosen chord. You could use that chord for a while, then choose a different chord for variety, or apply the variation methods described above to transform the same chord. The other voices, whether contrapuntal or used in other textures, can also make use of these same materials to give the piece cohesion.

So, based on simply choosing a few intervals or a favorite chord, we have several ways of spinning out a piece of music. Happy composing!

A piece of music, even an apparently very simple piece, presents to us a whole universe of ideas and approaches to them. We therefore need a way to organize these ideas in ways that help us to make sense of them, to understand better what the composer was trying to convey, and to become better composers ourselves.

One manner of doing so is dividing up a piece of music into its large component parts and further digging down into each of those areas, then putting it all back together, as if it were a sort of jigsaw puzzle, gradually revealing itself to us.

The questions I offer here should be viewed as practical points of departure for deeper analysis of both the structural and stylistic elements of compositions.

We look at a piece of music in its potential component parts: melody, counterpoint, harmony, variations, sectional forms, developmental forms, and serial and atonal methods.

Melody

We can further divide this down into pitch, rhythm and meter, contour, structure, and other elements.

-Pitch

What pitches are used in the melody? Do they form a scale?

Is there a pitch center? If so, how does it come to be established?

Are there any chromatic notes? How do they function?

If no traditional (common practice) pattern is used, can the pitch content be analyzed in terms of groupings of intervals?

-Rhythm and Meter

Is a metric grouping established?

What rhythmic patterns recur? How do these relate to the meter, if they do at all?

-Contour

Where are the cadences?

How do the phrases relate to each other? Are there instances of repetition, variation, contrast?

Are there small motives or melodic units that are being varied? If so, how?

Can the melody be reduced to an underlying pitch framework? How is this framework elaborated?

-Other

Consider: dynamics, text setting (if applicable), timbre, etc.

Counterpoint

What creates independence between the lines?

Is one line more important than another?

How do the lines relate to each other intervallically? What intervals or chords are used at opening and closing points? At other points?

Is a tonal center established? Is it the same in all the parts?

What is the rhythmic relationship between the lines? Do they trade these relationships?

Is imitation present? If so, describe its nature (between which voices, which intervals, time distance, strict canonic imitation, etc.)

How does each line develop? Does it use small melodic motives?

Are any contrapuntal techniques used? (Inversion, augmentation, diminution, etc.)

Is there invertible counterpoint present?

Is countermaterial used consistently?

Is there more than one important melodic idea presented?

How are the phrases constructed? Are cadences well-defined?

Is there a sectional plan to the piece?

How is overall form created in the composition?

Harmony

What sorts of sonorities are used? (triads, sevenths, nontertian, etc.)

How are the chords related to each other? Are the patterns of root movement?

Do the chords follow a large functional pattern?

Are some chords more important than others?

What sonorities are used cadentially?

How does the succession of chords relate to the rhythm and meter of the composition? Is there a prevailing harmonic rhythm?

Does the movement of the harmony help to establish the meter or work against it?

Is a tonal center established?

Are there changes of tonal center?

Are there changes of mode?

How do factors such as spacing, textural placement, and dynamics influence the harmony?

Variations

What is the basic material, or theme, of the work? Is it a melodic/rhythmic line, a harmonic pattern, a phrase structure, or tonal plan?

How is the material retained throughout the composition? Are any changes applied to the material itself?

How is the context around the material changed? Consider such things as texture, harmony, and rhythmic activity.

How many times is the basic material stated? Do these statements divide the composition into sections?

Is there any transitional material which is not a complete statement of the basic material? How is it related to the rest of the composition?

Does the composition suggest groupings of variations? Is there an overall formal pattern, such as ABA? If so, how does the composer accomplish these groupings? Are there returns of earlier variations?

Special Case: Cantus Firmus

Cantus Firmus treatment is often studied in a survey of variation techniques because one can frequently compare several different settings of the same cantus firmus and thus observe variant treatment.

What is the one line cantus firmus?

In which voice or voices does it occur?

How is it presented?

How do the other voices of the texture relate to the cantus firmus? Do they use motives from it?

Is there more than one statement of the cantus firmus?

Sectional Forms

Sectional form is a general term given to forms which have basically clearly defined and separable parts. Sectional forms such as ternary (ABA) or rondo can be more easily divided into independent units. Many characteristics of developmental forms are often combined with a simple sectional design.

What delineates sections? Are there changes of key, tempo, melodic materials, texture, etc.?

What is the internal phrase structure of each section?

How are the sections connected?

How many sections can clearly be identified?

Does a section return exactly within the piece?

What creates contrast between the sections? Are any elements retained from section to section?

What is the key scheme or cadential pattern of the work?

Are there any developmental aspects?

Developmental Forms

The term developmental forms usually refers to those compositions where development of material is a basic part of a formal design either in a separate section of the movement or throughout as an integral compositional process.

What determines the large sections of the work?

What is the basic material of the composition? Melodic lines? Rhythmic patterns? Chord progressions?

How is the material first presented?

How is it changed in the course of the composition? Is there a separate development section?

What elements are returned at the end of the movement?

Is it important to identify a second key area? Second thematic material?

Is there an introduction? A coda?

How are sections connected? Transitional material or abrupt change?

Serial and Atonal Compostions

What is the basic tone row?

How is it constructed? What intervals are used?

Does the row itself have any particular characteristics? Is it symmetrical, all-interval, etc.?

How does the composition use the row? In melodic lines? In chords? Are several row forms combined?

What are the audible organizing features of the composition? A certain texture, rhythmic pattern, melodic shape?

Are any of the elements of the row audible? Do interval patterns or row forms contribute clearly to the melodic, harmonic, or formal structure?

In atonal compositions not using a row structure, what is the basis for the pitch organization? Are there recurring chords or melodic units? Are there important pitch-class sets?

I owe a great debt of inspiration for this article to the work of Mary Wennerstrom, Ellis Kohs, and Reginald Smith Brindle.

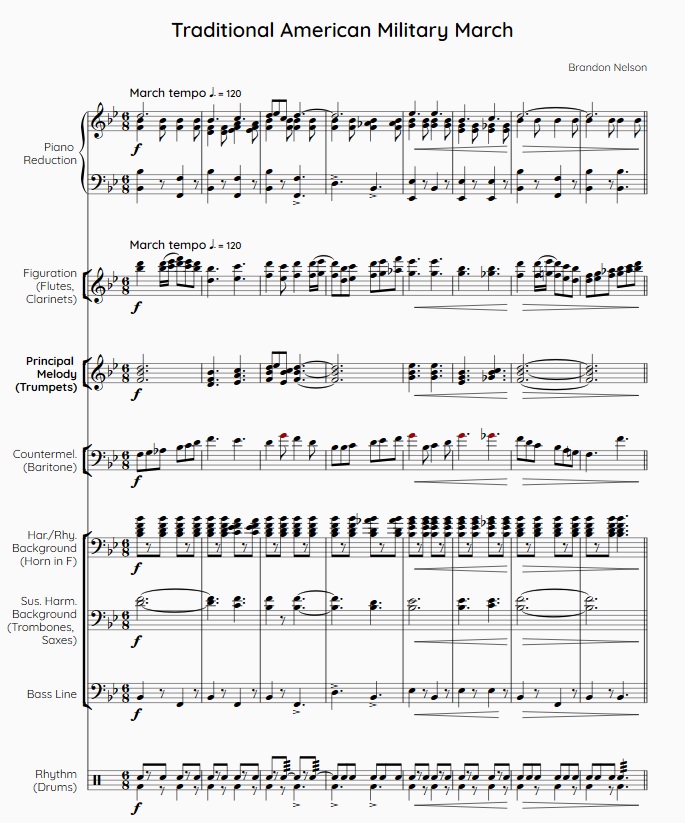

It shouldn’t surprise you that there exist literally thousands upon thousands of examples of this traditional American-style march. This march type used to be considered the popular music of its heyday (late 19th century into the early 20th century) and composers cashed in big time. Sousa, Fillmore, and King are the big names but there are hundreds of others who tried their hands at this march form.

Here’s how they work and how to write one of your own.

Prototypical Formal Outline

So stereotyped had the march form become that a conductor could say something like “go to the fourth measure of the second strain” and the band would know immediately what he was talking about. Publishers wouldn’t bother to print rehearsal numbers as it was seen as unnecessary. Everyone in a band would just be expected to know their way around a march. These days, put the numbers in.

All marches are in 6/8, alla breve, or 2/4 meter. Tempo generally varies between 120-132 to the beat (faster tempos can make certain figures unclear or nearly impossible to play accurately).

-Intro (4-8 bars, though this can be highly variable; sometimes in unison)

-First Strain (16 bars, usually with first-and-second ending repeat scheme)

-Second Strain (16 bars, usually with first-and-second ending repeat scheme; often the bass voices get the melody for at least the first portion of the strain)

-Trio (usually 32 bars; sometimes preceded by a brief fanfare-like introduction; sometimes repeated, sometimes this is where the march ends)

-Interlude (discordant passage colloquially referred to as “the dog fight” or “the break strain”; sometimes omitted; a distant cousin of the development section of a sonata, though there is no obligation to reuse motives or themes here)

-Final Strain (a recapitulation of the Trio; sometimes the strain is repeated, sometimes the repeat goes back to the Interlude, sometimes the repeat goes back to the Trio, depending on the wishes of the composer)

Obviously, there were exceptions, but this is the basic outline.

Harmonic and Other Stylistic Basics

-Intro: though usually in unison, there will generally be a strong implication of the dominant, which will logically flow into the first strain.

-First Strain: usually starts on the tonic chord and consists of two, eight measure phrases forming a complete period. The second one of these phrases often emphasizes the dominant to facilitate repeating back to the start of the strain.

-Second Strain: invariably starts on the dominant. It is quite common to make a diminuendo in the fourth measure and play the next four bars softly for contrast, though this is hardly mandatory. The second phrase of this strain would then return to a forte and from there pass through some form of subdominant harmony before concluding with the tonic of the original key. Again, the first ending usually prolongs the dominant to facilitate the repeat.

-Trio: almost always modulated to the subdominant key, in which the march will remain. This can end the march or go on to an interlude and be repeated.

Scoring Conventions

Simplicity is key. Marches sound more complex than they, musically, are. The primary objective in scoring marches for the band should be acquisition of a maximum volume from a minimum of parts–not instruments.

Marches thrive on music which has clear rhythms and simple, catchy tunes with a scored with a big sonority.

Some generalizations:

Flutes, first Bb clarinets: keep them on the melody or figuration.

Three part afterbeats in the middle register are adequate.

Vary the trombones with countermelodies, occasional afterbeats, and sustained harmony parts. Only the third trombone should be given unmelodic bass parts, and this very infrequently.

Score all major parts, melodic and harmonic, for the brass section.

Give variety to the baritone parts with principal melodies, obbligatos, and occasional harmony parts.

Allow the percussion section to carry the major part of the rhythm. It can do so without the assistance of the other sections if need be.

Use the trio of saxes (two alto, tenor) as a close-position chord unit. These instruments may be given melodies, obbligatos, figurations, and harmonic progressions.

A safe scoring plan is one which will sound complete with brass and percussion instruments only. The reeds provide interesting colors but the traditional-style march should be performable without any woodwinds. (Sorry guys.)

Secure contrast by means of dynamic changes rather than timbral subtleties.

Avoid simultaneous divisions in the clarinets, trumpets, and trombones.

Diversify horn parts by giving them sustained harmony progressions and occasional melodic and obbligato parts as a relief from unrelenting afterbeats.

One part should have rhythmic motion when its counterpart is comparatively inactive.

Marches scored for concert programs usually have some wind instruments playing afterbeats as a contrasting relief from the continuous use of percussion.

The usual breakdown of the various component parts are as follows: melody, rhythm parts, and the bass with optional harmonic figurations, obbligatos, and sustained harmony parts. The instruments of the band in the order of their importance, and listing of their basic functions, are as follows:

1. Trumpets – melody (unison or harmonized)

2. Percussion – rhythm

3. Trombones, Baritones, Saxes – harmony, countermelodies, rhythm

4. Basses – rhythm

5. Horns – harmony, rhythm, occasional countermelodies (unison or harmonized)

6. Flutes, Clarinets – figurations

Start composing with a simple piano reduction. Then flesh it out: score melody in trumpet trio. Compose figuration in flutes, clarinets. Write countermelody in baritones. Place sustained harmonic voicing in saxes, trombones. Horns on harmonic rhythm. Basses on bass line. Drums on rhythm.

In the trio it is not uncommon for the melody to be scored in the clarinets and baritones, in which case no countermelody should be used (figuration bursts in the upper octaves are ok).

An Example Illustrating the Above Principles

Often the intro is in unison, but as I’ve shown, it can work with more color too. I could write out an entire march, but I feel this example suffices to show how you might proceed with the rest of the march (the ideas of figuration, countermelody, and background figures and how they interact). And of course, nothing is better than studying scores and recordings of your favorite marches and applying ideas you like from that legwork.

I hope this helps you write your first march! If you have any questions or comments, please drop me a comment here or wherever this article was posted. Thanks!

Pax Aeterna (“the peace eternal”) is a musical plea for lasting peace in the world. Using a simple, plaintive melody as its basis, the band brings the listener through dramatic peaks and valleys reflecting on the struggle of realizing the goal of peace.

(This is a significant reimagining of an orchestral piece I composed by the same name a number of years ago.)

“Nebulae” is a collection of five short programmatic movements that represent the different types of these beautiful interstellar clouds of dust and particles.

MOVEMENTS:

I. Eta Carinae Nebula

II. Cat’s Eye Nebula

III. Great Nebula in Orion

IV. Iris Nebula

V. Eagle Nebula

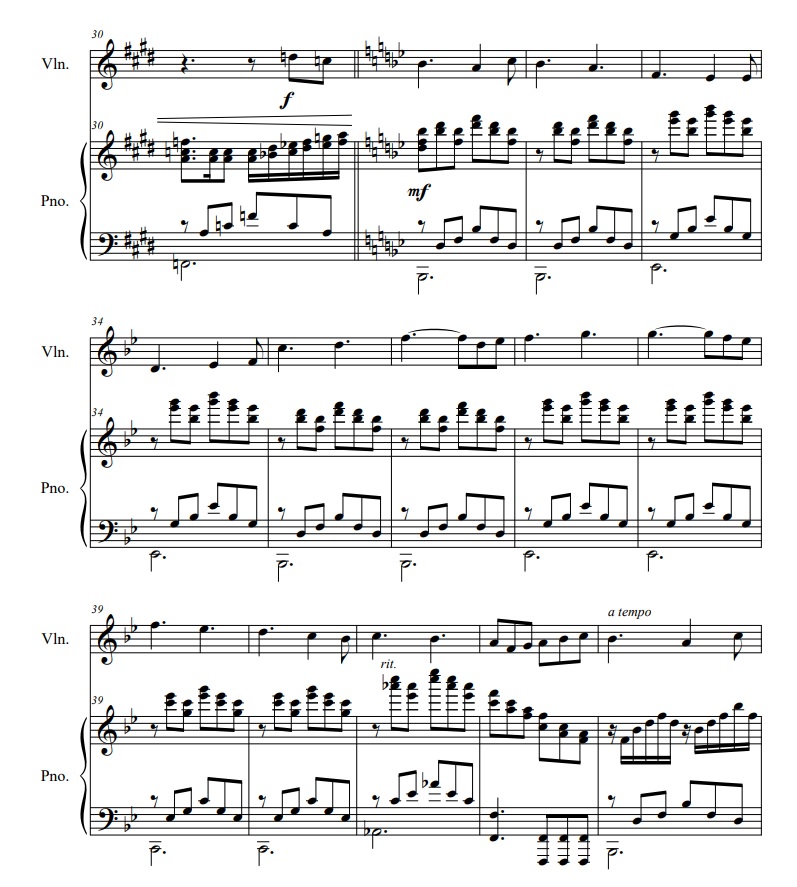

A beautiful solo for violin and piano, suitable to any occasion (though seems to be quite popular for weddings). Only modestly demanding in technique, any good high school violinist (and beyond) will love playing this.