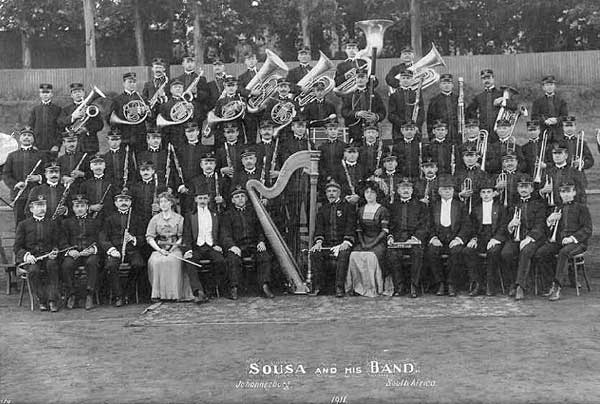

This is exactly what I look like.

My Roots and First Steps in Composition

The setting for our story: almost the exact middle of the upper peninsula of Michigan; small town, working class rust belt community with a community music tradition.

I started composing when I was 11 (around the time I joined the school band). David Dagenais was my first band teacher, and, as such, should immediately be canonized to the sainthood upon his death. I spent countless hours in his shadow, rattling off questions, proposing ideas, or just being a “middle school boy nuisance.” To his credit, he really did make several game attempts at teaching me formal music theory, but I had not the attention span for it at the time. I would just get a hold of manuscript paper and write whatever my ear dictated. It was mostly rubbish. I’m not just being modest. I was no Mozart.

Nevertheless, by my 8th grade year, I had listened to enough classical cassette tapes (“Hooked on Classics”, man!) and been exposed to a sufficient amount of concert band repertoire (I was James Swearingen’s number one fan) that I could put together a reasonably-coherent overture for my peers to perform at the Spring Concert that year. My mother attempted to record it with one of those gargantuan “camcorder” devices that we had back in the day, but mostly you hear her whispering to others about how it was me up there on the podium. (Again, history really has not been robbed of anything here.)

My high school years continued in much the same fashion: trailing the somehow-patient Mr. Dagenais (to be replaced by a similarly tolerant Dennie Korpi my Junior Year), cranking out an ever-increasing quantity (and slowly-increasing quality) of compositions, while stubbornly continuing to resist training in music theory.

By the end of my Senior Year, and, having gained entry into the music school at Northern Michigan University, I finally succumbed and borrowed one of Mr. Korpi’s theory textbooks. Naturally, I psychically kicked myself quite thoroughly for not so training myself in prior years. (I should note that I don’t take the pedantic view that one needs to be a master of common practice music theory to be a fine composer, but that I do believe it instills in one a certain vital discipline for arraying tones in such a way as to fulfill elementary psychological expectations; from there, one may go ahead and break such conventions, or come up with new ones, as one’s artistic voice requires.)

College, as usually it is, was a mind-blowing adventure on a near daily basis. I was literally the second person in the music building each morning (I was a commuter student and I hated having to wait for a parking spot), the first being the genial and wise Dr. Floyd Slotterback. By title he was the director of the choral program, but to me, he was much more. He would invite me to sit across from him with a cup of coffee and just talk. Sometimes it would be the news, sometimes it would be family and friends, but on the most stimulating days, he would unfurl his massive intellect and teach me something about my own compositions, or hold court on a particular recording he was listening to. I remember the first time he played a Conlon Nancarrow album and I couldn’t get out of my seat for a good half hour. I didn’t know music like that was even possible. My world, in other words, was being blown and rebuilt.

As with most composers, just about all of the professors I had could merit their own admiring paragraph. But one more, and most deserving: Dr. Stephen Grugin. Yes, he was the collegiate band director, but there always seemed to be something more to find behind that unassuming Kentuckian facade. And, to his (mostly) hidden chagrin, I made it my mission to find every last bit. Not only was he actively interested in my voracious compositional appetite, but he seemed to “get it” in a way that few others did. A young family man at the time, I have no idea from where he found the energy or mental space for a task as large as me, yet bless him for doing so. Every concert band score I came up with (and there started to be a lot of them–especially after I learned more about music theory and how to use computer engraving software), he would not just look at, but he would take his pencil out and make careful notes in the margins, taking the time to explain what I was doing, and how it might be improved. It is Dr. Grugin I credit with ultimately encouraging me to pursue composition seriously and so too it is his guidance that made me qualified to do so.

In graduate school, at Central Michigan University, I had the privilege of studying with Jose-Luis Maurtua my first semester. Not as well-known as some of his faculty colleagues, the man was a brilliant teacher and composer who died far too young. I credit him with making me see the subtle building blocks that make up the scaffolding of a composition. The remainder of my time I studied with David Gillingham, whom you may have heard of. He was classy, meticulous, and only said a critical word as a very last resort. I don’t think I could necessarily tell you a specific concept or “trick” he passed on to me, but I can assure you that Dr. Gillingham’s enormous gifts as a teacher lie far more in his ability to encourage his students to keep pushing up that unforgiving mountain we call composition. Some mentors don’t hesitate to tear apart whatever is put in front of them (and maybe some students learn well that way), but “Doc” always made sure you left your lesson at the very least confirmed that you would keep on trying.

LESSONS FROM HISTORY, BUILDING MY OWN

I’ve dabbled in just about every school of composition there is (though I never really got into electronic music). In the end, I always felt more at home when working within the idiom of ancient music. Machaut became (and remains) a particular favorite. His Messe de Nostre Dame is considered by many to be his magnum opus, which I’d like to share with you below. His influence on my formation is not just spiritual but also technical. I don’t infrequently make use of the “color/talea” concept that he made frequent use of and was generally popular in this period of music history. “Color” refers to a fixed set of pitches and “talea” is a rhythm that is of a different length than the pitch set. Combining the two can often result in interesting combinations!

Machaut – Messe de Nostre Dame

While I don’t see Bach as “ancient,” he is an inexhaustible source of inspiration! I often find he leads me to Paul Hindemith, who, when he reached his maturity, aspired to make of himself something of a Bach-like figure for his creative epoch. He didn’t much care for unrestricted atonality but he was a firm believer that nontonal music could be given what was, to him, a coherent philosophical and acoustical sense of organization. Both his ideas and his music left a significant impact on me during my student years, and I still believe his numerous books are worthwhile reading. His music (especially Mathis der Maler) is quite powerful.

Hindemith – Mathis der Maler (symphonic setting)

I don’t like Schoenberg. I respect the “liberation of the possible” he opened the gate to, but I don’t think I’ve ever voluntarily listened to any of his actual music. Same of his disciple Berg. Ironically, I find something of a kindred spirit in Webern. He shares many broad traits I value as a composer: he knew what he wanted to say and exactly how he wanted to say it and didn’t waste a single note. He remains the king of economic means. His symphony is less than 10 minutes long, yet it is perfection of proportion! I realize he will never have many fans, but I stand by him, both as a composer and a music lover.

Webern – Symphony op. 21

Ligeti wrote music that I find quite intelligent, moving, and innovative, yet isn’t necessarily “repellent” in the sense of overwrought dissonance or unintelligibility. I particularly recommend his Musica Ricercata. Study it first. Then listen. Or don’t bother studying it. Still absolute brilliance!

Ligeti – Musica Ricercata

Shostakovich was a truly amazing creative force sadly tamped down by a maniac. His middle symphonies are treasures of economy and expressive power (you might be noting a trend forming in those aesthetics I value in my own composing). And his piano preludes and fugues (a la Bach) are a joy to hear despite (or perhaps because of) their almost elementary means.

Shostakovich – Preludes and Fugues op. 87

Messiaen might be one of my overall favorite composers. His craft was so daringly sophisticated and beautiful that his work is often regarded as consisting of its own “school”. If you haven’t read the little book he wrote on his musical language, I very strongly suggest it (his wonderful, mystic charm shines through best in the original French, but the English translation is quite good as well). His ideas on rhythm (he liked especially what we would call palindromes), his plainsong-inspired sense of metric freedom, his idiosyncratic ideas of special types of pitch modes, his inspired sense for the beautifully unique qualities of every instrument and combination of instruments in the orchestra—these are his legacy from which I, and many other composers, have drawn great inspiration. There are so many phenomenal pieces I could ask you to hear, but this one is a good distillation of his mature style and also an exposition of his profound Catholic faith.

Messiaen – Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant Jésus

Digging perhaps most deeply into my own aesthetics as a composer, one finds Vincent Persichetti. His creative inspiration was seemingly limitless! The work is serious yet, if you listen attentively, dryly witty. His sense for harmony and timbre are, to me, piquant, colorful, and poignant. I absorbed much of his craft into my own. (He also wrote a book, which I absolutely think you should read.) I feel like Persichetti gave me, in the latter days of my student years, permission to not only write with logic and economy, but with a kind of freedom I couldn’t even imagine at that point in my artistic formation. I still go back to his scores whenever I feel “stuck.” Persichetti left a heavy footprint in many musical mediums, but I feel most closely attached to his concert band repertoire. This is an example of his brilliant use of color, sense of drama, and that harmonic sensibility which never loses its poignancy:

Persichetti – Psalm for Band

I feel I must at least mention Arvo Pärt. Some dismiss his work as archaic or simplistic, but they miss the point. He takes much inspiration from the heritage of his ancient faith, particularly that of Gregorian chant, aspects or principles of which can be found throughout his oeuvre. He is not content to make use of the treasures of the Church, though. He has innovated as well, such as coming up with a compositional method called “tintinnabuli,” inspired by the echoing of Church bells. Pärt’s contribution to my work is more conceptual–that simple means are not always trite–indeed, they can be just what is demanded. Perhaps the piece of his that most moves me is his tribute on the passing of another great composer, Benjamin Britten:

Pärt – Cantus In Memoriam Benjamin Britten

There are so many more composers and concepts I could delve into, both in terms of musical criticism and personal influences, but I think I have amply covered the thesis of this essay. From the foregoing, I believe you have a good idea of what I value as a creator and in other creators. I encourage you to explore this website to learn more about my music and even hear some of it if you like:

The Music of Brandon Nelson

Please Share This Article!