It shouldn’t surprise you that there exist literally thousands upon thousands of examples of this traditional American-style march. This march type used to be considered the popular music of its heyday (late 19th century into the early 20th century) and composers cashed in big time. Sousa, Fillmore, and King are the big names but there are hundreds of others who tried their hands at this march form.

Here’s how they work and how to write one of your own.

Prototypical Formal Outline

So stereotyped had the march form become that a conductor could say something like “go to the fourth measure of the second strain” and the band would know immediately what he was talking about. Publishers wouldn’t bother to print rehearsal numbers as it was seen as unnecessary. Everyone in a band would just be expected to know their way around a march. These days, put the numbers in.

All marches are in 6/8, alla breve, or 2/4 meter. Tempo generally varies between 120-132 to the beat (faster tempos can make certain figures unclear or nearly impossible to play accurately).

-Intro (4-8 bars, though this can be highly variable; sometimes in unison)

-First Strain (16 bars, usually with first-and-second ending repeat scheme)

-Second Strain (16 bars, usually with first-and-second ending repeat scheme; often the bass voices get the melody for at least the first portion of the strain)

-Trio (usually 32 bars; sometimes preceded by a brief fanfare-like introduction; sometimes repeated, sometimes this is where the march ends)

-Interlude (discordant passage colloquially referred to as “the dog fight” or “the break strain”; sometimes omitted; a distant cousin of the development section of a sonata, though there is no obligation to reuse motives or themes here)

-Final Strain (a recapitulation of the Trio; sometimes the strain is repeated, sometimes the repeat goes back to the Interlude, sometimes the repeat goes back to the Trio, depending on the wishes of the composer)

Obviously, there were exceptions, but this is the basic outline.

Harmonic and Other Stylistic Basics

-Intro: though usually in unison, there will generally be a strong implication of the dominant, which will logically flow into the first strain.

-First Strain: usually starts on the tonic chord and consists of two, eight measure phrases forming a complete period. The second one of these phrases often emphasizes the dominant to facilitate repeating back to the start of the strain.

-Second Strain: invariably starts on the dominant. It is quite common to make a diminuendo in the fourth measure and play the next four bars softly for contrast, though this is hardly mandatory. The second phrase of this strain would then return to a forte and from there pass through some form of subdominant harmony before concluding with the tonic of the original key. Again, the first ending usually prolongs the dominant to facilitate the repeat.

-Trio: almost always modulated to the subdominant key, in which the march will remain. This can end the march or go on to an interlude and be repeated.

Scoring Conventions

Simplicity is key. Marches sound more complex than they, musically, are. The primary objective in scoring marches for the band should be acquisition of a maximum volume from a minimum of parts–not instruments.

Marches thrive on music which has clear rhythms and simple, catchy tunes with a scored with a big sonority.

Some generalizations:

Flutes, first Bb clarinets: keep them on the melody or figuration.

Three part afterbeats in the middle register are adequate.

Vary the trombones with countermelodies, occasional afterbeats, and sustained harmony parts. Only the third trombone should be given unmelodic bass parts, and this very infrequently.

Score all major parts, melodic and harmonic, for the brass section.

Give variety to the baritone parts with principal melodies, obbligatos, and occasional harmony parts.

Allow the percussion section to carry the major part of the rhythm. It can do so without the assistance of the other sections if need be.

Use the trio of saxes (two alto, tenor) as a close-position chord unit. These instruments may be given melodies, obbligatos, figurations, and harmonic progressions.

A safe scoring plan is one which will sound complete with brass and percussion instruments only. The reeds provide interesting colors but the traditional-style march should be performable without any woodwinds. (Sorry guys.)

Secure contrast by means of dynamic changes rather than timbral subtleties.

Avoid simultaneous divisions in the clarinets, trumpets, and trombones.

Diversify horn parts by giving them sustained harmony progressions and occasional melodic and obbligato parts as a relief from unrelenting afterbeats.

One part should have rhythmic motion when its counterpart is comparatively inactive.

Marches scored for concert programs usually have some wind instruments playing afterbeats as a contrasting relief from the continuous use of percussion.

The usual breakdown of the various component parts are as follows: melody, rhythm parts, and the bass with optional harmonic figurations, obbligatos, and sustained harmony parts. The instruments of the band in the order of their importance, and listing of their basic functions, are as follows:

1. Trumpets – melody (unison or harmonized)

2. Percussion – rhythm

3. Trombones, Baritones, Saxes – harmony, countermelodies, rhythm

4. Basses – rhythm

5. Horns – harmony, rhythm, occasional countermelodies (unison or harmonized)

6. Flutes, Clarinets – figurations

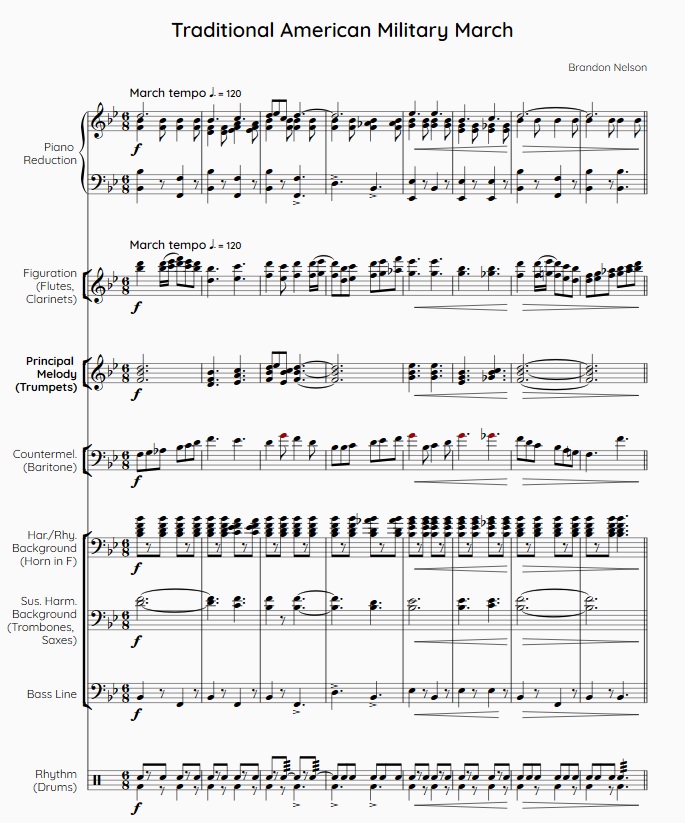

Start composing with a simple piano reduction. Then flesh it out: score melody in trumpet trio. Compose figuration in flutes, clarinets. Write countermelody in baritones. Place sustained harmonic voicing in saxes, trombones. Horns on harmonic rhythm. Basses on bass line. Drums on rhythm.

In the trio it is not uncommon for the melody to be scored in the clarinets and baritones, in which case no countermelody should be used (figuration bursts in the upper octaves are ok).

An Example Illustrating the Above Principles

Often the intro is in unison, but as I’ve shown, it can work with more color too. I could write out an entire march, but I feel this example suffices to show how you might proceed with the rest of the march (the ideas of figuration, countermelody, and background figures and how they interact). And of course, nothing is better than studying scores and recordings of your favorite marches and applying ideas you like from that legwork.

I hope this helps you write your first march! If you have any questions or comments, please drop me a comment here or wherever this article was posted. Thanks!

Leave a comment